Harry Semmes was not a warrior by nature. Although a friend and contemporary of George S. Patton, Semmes displayed none of the self-promotion nor love of armed conflict embodied by “Old Blood and Guts.” He answered when his country called, in two World Wars, and emerged with an impressive array of medals and citations. After each war, he returned to his civilian law practice and his favorite sporting pastime—foxhunting.

Semmes came to hunting via an odd path: neurological therapy. He’d already been awarded his first Distinguished Service Cross, in 1918, for rescuing his tank driver from the middle of a swollen river under heavy enemy fire. (The DSC is America’s second-highest battlefield award, ranking only behind the Medal of Honor.) Two weeks later, while leading an armored attack on foot through the nightmarish landscape of the Argonne, Capt. Semmes was struck in the back of the head by a German bullet. His commanding officer, Col. George Patton, received a leg wound that same day.

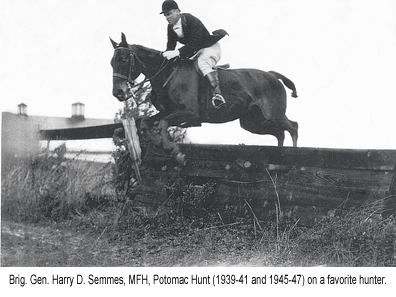

The injury damaged the portion of the brain that controls balance, leaving Semmes reeling when he tried to walk. His doctor suggested some amount of recovery was possible with proper stimulation. Upon returning home to Maryland, he took up horseback riding. What better way to stimulate balance than falling off a horse every time you try to mount? This went on for six months. But Harry Semmes stuck with it and after just one year he was following hounds, and jumping stone walls and fences, with the Riding and Hunt Club of Washington (forerunner of today’s Potomac Hunt Club).

Semmes answered the call again when World War II began in 1941, even though he was then fifty years old. Thanks to the influence of his good friend General Patton, the “permanently disabled” stamp on his WWI discharge papers was overlooked and now Lt. Col. Semmes was assigned to the Second Armored Division. He won his third DSC when American forces began action in North Africa, defending the landing effort in Morocco against fierce German resistance.

His heroism was also recognized by other appreciative nations including Great Britain (“For God and the Empire”), France (Merit of War), Italy (Crocci di Guerra), and Brazil (Merito de Guerra).

Again, Harry Semmes returned to his Maryland farm, his family, his law practice, and the Potomac Hunt Club where he was Master of Foxhounds. Semmes continued to serve his country in peacetime, as an instrumental force in creating the Army Reserve Program and later as part of the effort to accelerate the full racial integration of the U.S. Army.

Through the gracious generosity of General Semmes’s sons—David, Harry, and J. Gibson Semmes—the Museum is pleased to report the gift of items from their father’s distinguished career. These include a photograph from his hunting days with Potomac, his vintage 1920s dress scarlet with silver RHCW buttons, and miniaturized decorations worn with dress scarlet (three DSCs with two oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, European Campaign). The donation also includes the book Lights Along the Way, Great Stories of American Faith, by Thomas Fleming, which features a section (pp 185-192) titled “Harry Semmes and The Soul of America” (and from which much of the information for this article was drawn).

There is a wide range of reasons why people come to mounted hunting. A bullet to the head is not one of the more common inspirations. But the sport helped Harry Semmes recover his physical balance, sufficiently to serve his country yet again and face incredible dangers without regard for his own safety. That his sense of balance extended to all aspects of his life—public service, professional practice, family, and sport—is a testament to this man’s determination and concern for the greater good.

We are honored to include a portion of his legacy in the Museum’s collection.